History of Computer PDF: An Article Plan

This article explores the fascinating evolution of computing, from ancient tools like the abacus

to modern microprocessors and the rise of digital documents like PDF.

The journey of computing is a remarkable tale of human ingenuity, spanning millennia and marked by pivotal breakthroughs. From rudimentary counting tools to the sophisticated digital systems we rely on today, the evolution has been relentless. Initially, computation involved manual methods, exemplified by the abacus – a device dating back to 2600 BC – facilitating basic arithmetic.

The 17th century witnessed the emergence of mechanical calculators, like Pascaline and Leibniz’s machine, automating calculations. However, the true conceptual leap came with Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine in the 1830s, laying the groundwork for modern computers. The 20th century ushered in the era of electronic computation, with machines like ENIAC and UNIVAC I, marking the first and second generations, respectively. This progression ultimately paved the way for the digital revolution and the ubiquitous presence of computers in modern life.

Precursors to Modern Computers (Before 1940)

Before the advent of electronic computers, several ingenious devices and concepts laid the essential foundations. The abacus, originating around 2600 BC, served as an early aid to calculation, demonstrating humanity’s innate desire to automate computation. Centuries later, in the 17th century, Blaise Pascal’s Pascaline and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s calculator represented significant steps towards mechanical computation.

However, it was Charles Babbage’s 19th-century Analytical Engine that truly foreshadowed modern computers. Though never fully realized in his lifetime, its design incorporated key elements like an arithmetic logic unit, control flow, and memory. Early 20th-century developments included machines designed to solve specific mathematical functions, like differential equations, further refining computational approaches before the electronic age truly began.

The Abacus: Early Calculation (2600 BC)

Dating back to approximately 2600 BC, the abacus represents one of the earliest known tools for calculation. Originating in Mesopotamia and later refined in China, this manual aid utilized beads arranged on rods or in grooves to represent numerical values. Skilled operators could perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division with remarkable speed and accuracy.

While not a computer in the modern sense, the abacus embodies the fundamental principle of representing information and manipulating it according to defined rules. It demonstrates a crucial early step in humanity’s quest to automate and simplify complex calculations, paving the way for future computational devices. Its enduring use for centuries highlights its practical effectiveness and conceptual importance.

Pascaline and Leibniz Calculator (17th Century)

The 17th century witnessed significant strides in mechanical calculation with the inventions of Blaise Pascal’s Pascaline (1642) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s stepped reckoner. Pascal’s device, designed to aid his father’s tax work, could perform addition and subtraction using geared wheels. Leibniz’s calculator, building upon Pascal’s work, aimed for multiplication and division through a stepped drum mechanism.

Though innovative, these machines were complex and expensive to build, limiting their widespread adoption. They represented crucial conceptual leaps, however, demonstrating the feasibility of automating arithmetic operations mechanically. These early calculators laid the groundwork for future advancements, showcasing the potential for machines to alleviate the burden of tedious calculations and foreshadowing the digital revolution.

Charles Babbage and the Analytical Engine (1830s)

Charles Babbage, a British polymath, conceived of the Analytical Engine in the 1830s, a design remarkably prescient of modern computers. Unlike previous calculators focused on specific operations, Babbage’s engine was intended as a general-purpose mechanical computer. It incorporated an “arithmetic logic unit” (the mill), memory (the store), and input/output mechanisms using punched cards – inspired by the Jacquard loom.

Ada Lovelace, often considered the first computer programmer, wrote an algorithm for the Analytical Engine. Despite Babbage’s extensive efforts, the machine was never fully constructed due to technological limitations and funding issues. Nevertheless, its design established fundamental concepts central to computer architecture, solidifying Babbage’s legacy as a visionary pioneer.

First Generation Computers (1946-1959): Vacuum Tubes

The first generation of computers, spanning 1946-1959, relied on vacuum tubes for circuitry. These bulky, energy-intensive tubes generated significant heat and were prone to failure, making these early machines large and unreliable. Despite these limitations, they marked a monumental leap forward in computing capability.

Programming was primarily done in machine language, a tedious and error-prone process. Magnetic drums and punched cards served as primary storage. Key examples include ENIAC and UNIVAC I, pioneering machines that demonstrated the potential of electronic computation for scientific and commercial applications, laying the groundwork for future advancements.

ENIAC: The First Electronic General-Purpose Computer

The Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), completed in 1946, is widely considered the first electronic general-purpose computer. Developed during World War II, it was initially designed to calculate ballistic firing tables for the U.S. Army. ENIAC was massive, occupying a large room and utilizing over 17,000 vacuum tubes.

Its programming involved physically rewiring the machine, a complex and time-consuming task. Despite its limitations, ENIAC demonstrated the power of electronic computation and paved the way for more flexible and programmable computers. It represented a significant advancement over previous electromechanical devices, marking a pivotal moment in the history of computing technology.

UNIVAC I: The First Commercial Computer

The Universal Automatic Computer I (UNIVAC I), delivered to the U.S. Census Bureau in 1951, holds the distinction of being the first commercially produced electronic digital computer. Unlike ENIAC, which was built for a specific government purpose, UNIVAC I was designed for broader business and administrative applications.

It utilized magnetic tape for input and output, a significant innovation at the time, and could handle both numeric and alphabetic data. UNIVAC I’s adoption by businesses signaled the beginning of the commercial computer era, demonstrating the potential of computers beyond scientific and military calculations. Its success established a foundation for the future development and widespread use of computers in various industries.

Second Generation Computers (1959-1965): Transistors

The second generation of computers, spanning from 1959 to 1965, marked a pivotal shift from bulky vacuum tubes to smaller, more reliable transistors. This transition dramatically reduced the size, power consumption, and cost of computers, while simultaneously increasing their speed and efficiency.

Transistors allowed for faster processing speeds and greater dependability, leading to more sophisticated applications. Programming languages like FORTRAN and COBOL emerged during this period, simplifying software development. This era witnessed the rise of batch processing systems and the increasing use of magnetic core memory. The transistor’s impact was transformative, paving the way for more accessible and powerful computing.

The Rise of Transistor Technology

The invention of the transistor at Bell Labs in 1947 revolutionized electronics, and subsequently, computing. Replacing vacuum tubes, transistors offered significant advantages: smaller size, lower power consumption, increased reliability, and reduced cost. This breakthrough enabled the creation of more compact and efficient computers.

Early transistors were initially expensive to manufacture, but advancements in production techniques quickly lowered costs. The transition from vacuum tubes to transistors wasn’t immediate, but by the late 1950s, transistors had become the dominant technology in computer construction. This shift fueled the second generation of computers, marking a substantial leap forward in computing power and accessibility, setting the stage for future innovations.

IBM 1401: A Popular Business Computer

Introduced in 1959, the IBM 1401 was a massively successful, transistorized computer specifically designed for business and commercial applications. Unlike its predecessors, it utilized magnetic tape and core memory, making it faster and more versatile for data processing tasks. Its architecture was optimized for handling large volumes of input and output, crucial for businesses managing growing datasets.

The 1401’s popularity stemmed from its affordability and ease of use, alongside IBM’s robust support and marketing. It became a staple in businesses, universities, and government agencies, processing payroll, inventory, and other essential functions. Over 10,000 units were sold, solidifying IBM’s dominance in the burgeoning computer market and accelerating the adoption of computing technology in the business world.

Third Generation Computers (1965-1971): Integrated Circuits

The mid-1960s marked a pivotal shift with the advent of the integrated circuit (IC), or “chip.” This innovation allowed for placing numerous transistors onto a single silicon wafer, dramatically reducing size, cost, and increasing speed and reliability. Third-generation computers, leveraging ICs, were significantly smaller, faster, and more energy-efficient than their predecessors.

This era saw the rise of minicomputers, making computing accessible to more organizations. Time-sharing became prevalent, enabling multiple users to access a single computer simultaneously. The development of operating systems became more sophisticated, managing resources and simplifying programming. This generation laid the groundwork for the future of computing, paving the way for the microprocessor revolution.

The Development of the Integrated Circuit (IC)

The integrated circuit, a cornerstone of modern computing, wasn’t a singular invention but the result of collaborative efforts. Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments and Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor independently conceived of the IC in 1958 and 1959, respectively. Kilby demonstrated the first working IC, while Noyce’s version proved more practical for mass production.

This breakthrough involved fabricating multiple electronic components – transistors, resistors, and capacitors – onto a single semiconductor material, typically silicon. The IC dramatically reduced the size and cost of electronic circuits, while simultaneously boosting performance and reliability. This innovation fueled the third generation of computers and continues to drive technological advancements today.

IBM System/360: A Family of Compatible Computers

Launched in 1964, the IBM System/360 represented a paradigm shift in computing. Unlike previous systems, the S/360 wasn’t a single machine, but a family of computers, ranging in price and performance. Crucially, all models within the family could run the same software, offering unprecedented compatibility and scalability for businesses.

This compatibility was achieved through a standardized architecture and instruction set. The S/360 utilized integrated circuits extensively, contributing to its improved performance and reduced size. It became immensely popular, dominating the mainframe market and establishing IBM as a leading force in the computer industry. The S/360’s influence continues to be felt in modern computer architecture.

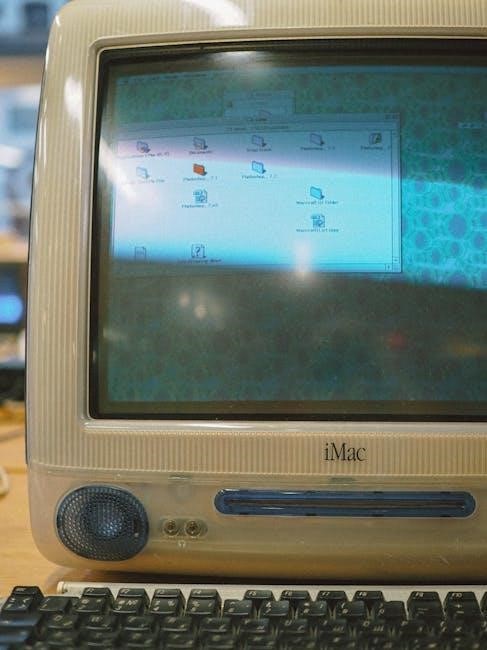

Fourth Generation Computers (1971-Present): Microprocessors

The fourth generation, beginning around 1971, is defined by the invention of the microprocessor. This single chip contained all the central processing unit (CPU) functions, dramatically reducing size and cost. Intel’s 4004, released in 1971, is widely considered the first commercially available microprocessor, initiating the personal computer revolution.

Microprocessors enabled the development of smaller, more affordable computers accessible to individuals and small businesses. This era saw the rise of companies like Apple and Microsoft, and the proliferation of personal computers. Continued advancements in microprocessor technology – increasing speed, capacity, and efficiency – drive innovation to this day, shaping the digital landscape we know.

Intel 4004: The First Microprocessor

Released in November 1971 by Intel, the 4004 marked a pivotal moment in computing history. Initially designed for a Japanese calculator company, Busicom, it was the first commercially available single-chip microprocessor. Though limited by today’s standards – containing 2,300 transistors – it demonstrated the feasibility of integrating an entire CPU onto one chip.

The Intel 4004’s creation spurred rapid innovation, paving the way for more powerful and versatile microprocessors. Its 4-bit architecture, while basic, proved the concept and ignited the personal computer revolution. This breakthrough dramatically reduced the size and cost of computing, making it accessible beyond large corporations and institutions, fundamentally altering the technological landscape.

The Personal Computer Revolution

The advent of the microprocessor, particularly Intel’s 4004, fueled the personal computer (PC) revolution in the 1970s and 80s. Early machines like the Altair 8800 (1975) sparked hobbyist interest, while companies like Apple, Commodore, and IBM soon entered the market with more user-friendly systems.

The IBM PC (1981) became a dominant force, establishing a standard architecture. This era witnessed the rise of software applications – word processors, spreadsheets, and games – making computers valuable tools for individuals and businesses. The decreasing cost and increasing accessibility of PCs democratized computing, shifting it from centralized mainframes to individual desktops, forever changing how people worked and lived.

The Emergence of PDF and Digital Documents

Before PDF, sharing digital documents reliably was a challenge. Early formats were often platform-dependent, meaning a document created on one computer might appear differently – or not at all – on another. PostScript, developed by Adobe in the 1980s, was a page description language, but lacked the portability needed for widespread document exchange.

The need for a universal document format, preserving fonts and layout across different systems, became increasingly apparent. This paved the way for Adobe’s creation of the Portable Document Format (PDF) in 1993. PDF aimed to provide a consistent viewing experience, regardless of the operating system or software used, revolutionizing document sharing and archiving.

Early Digital Document Formats

Prior to PDF’s arrival, several digital document formats existed, each with limitations. Early word processors like WordStar and WordPerfect used proprietary formats, hindering interoperability. These formats often relied on specific software to open and view correctly, creating compatibility issues when sharing files between different systems.

PostScript, while a significant step forward, was primarily a page description language for printers, not a user-friendly document format for general exchange. Hypertext formats also emerged, but focused on linking rather than precise document layout. The lack of a standardized, platform-independent format meant digital documents were often fragile and prone to rendering errors.

Adobe and the Creation of PDF (1993)

In the early 1990s, Adobe recognized the growing need for a digital document format that preserved formatting across different platforms. Led by Charles Geschke, Adobe introduced the Portable Document Format (PDF) in 1993 as an open standard. The initial goal was to simplify document exchange, ensuring consistent appearance regardless of the operating system or software used to view it.

PDF cleverly encapsulated fonts, images, and layout information within a single file. This innovation solved the interoperability problems plaguing earlier formats. Adobe provided free readers and viewers, accelerating PDF’s adoption. It quickly became the standard for reliable document sharing and archiving, fundamentally changing how information was distributed.

Impact of Computers and PDF on Society

The proliferation of computers and the subsequent creation of PDF have profoundly reshaped society. Computers revolutionized communication, commerce, and access to information, fostering globalization and accelerating innovation across all sectors. PDF, in turn, streamlined document management, enabling efficient archiving, secure distribution, and reliable reproduction of critical information.

This combination facilitated remote work, online education, and digital publishing. Legal, academic, and governmental processes became more efficient with standardized digital documentation. The ease of sharing and preserving knowledge via PDF has democratized access to information, empowering individuals and fostering collaboration on a global scale, fundamentally altering how we learn, work, and interact.